Lawrence of Arabia: the Plymouth years

Lawrence of Arabia: the Plymouth years

14.09.13 3 comments

A SCRUFFY, thirty-something man called Shaw in ragged clothes walks into an RAF recruitment office to apply for a job.

No wonder he looks rough: he's been living in the sidecar of his motorbike.

There's no surprise, either, that the man behind the desk throws the would-be airman out of the office.

The newest, most glamorous branch of the British Armed Forces is not short of younger, fitter, more smartly-dressed men eager to join its ranks.

But the RAF hopeful does not give up. He returns a few minutes later with an official from the Air Ministry to vouch for him and is immediately accepted.

The recruit was clearly a man with connections – in fact he was one of the most enigmatic heroes of 20th century Britain: Lawrence of Arabia. At the time he was world famous as the man who united Arab tribes to back the British cause in World War I. That surreal episode in the recruitment office in London would lead to a connection with Plymouth as the rather-less-celebrated Shaw of Mount Batten.

The gem of a story above comes from George Williams of Torpoint who has been fascinated by T E Lawrence for more than 50 years.

George is so focused that he meticulously switches between using Lawrence and Shaw when talking about the Arabian adventures and the hero's four years in Plymouth.

He honours his subject's wish to put the past behind him, the reason why former Army colonel Lawrence chose to join the RAF and ended up in the base at Mount Batten.

George has one eye on the present, though, to show just how influential Lawrence once was.

"I look at Syria and the Middle East today and it's an absolute melee," says George. "He forecast that scene in 1921 and tried to change the borders in the region."

Lawrence had pulled together the previously infighting Arab tribes with the promise of a homeland after the 1914-18 conflict.

Another admirer of Lawrence's exploits goes further. If his plan to give the united tribes their own nation had been allowed there would have been peace in the Middle East today, believes Plymothian Rory Allen.

Lawrence tried to make good on the promise when he was involved in international post-war discussions on the Middle East in 1921/22, also involving Winston Churchill (who would lead Britain as Prime Minister in World War II).

When he failed he became disillusioned and disappointed. He turned his back on public life, changed his name to Shaw, joined the RAF as a humble aircraftman and arrived in Plymouth in 1929.

"He arrived from India – which he'd had to leave because of talk in the press that he was involved in espionage – on a liner-cum-trader, Rawalpindi," says George.

"There was a pile of correspondence waiting for him. Anything addressed to Lawrence of Arabia or TE Lawrence he threw into the Sound without opening.

"He only read what was addressed to TE Shaw."

While 338171A/C Shaw, TE wanted to forget his past, he did not turn his back on old friends.

Lawrence would cruise across from Mount Batten to the Barbican on his boat, Biscuit, to meet up with James Vincent, a sergeant in the Devonshire Regiment who he'd served with in the war in the Middle East.

"That old soldier was my grandfather," says Rory, of Efford. "He lived in Lambhay Hill.

"He'd served in a liaison unit in Iraq, Syria, and Egypt.

"They'd have a beer or two in the Mayflower pub (a Blitz casualty in World War Two).

"When I was a kid living in the Barbican my grandad would tell me bits about being in the war in Mesopotamia (part of present-day Iraq) with Lawrence.

"Lawrence was a genius. He spoke at least seven different Arabic dialects. He wasn't strong physically, but he was very strong mentally.

"He was very charming and friendly but could also be very secretive."

Lawrence also struck up new friendships in Plymouth. He loved motorbiking and met up with other enthusiasts on Sundays at the Rock, Yelverton. One of the bikers was Devon and Cornwall speedway champion Ted McSweeney, who lived in St Budeaux.

"They'd go out across Dartmoor and around north Devon," says Ted's son, Ray, who also lives in St Budeaux.

"Dad worked in the dockyard as an engineer and Lawrence was an engineer too. I suppose they had that in common as well as the bikes.

"They got quite friendly.

"Dad would be on his KTT Velocette and Lawrence would always draw away on his Brough because it was big and powerful. But they'd always catch him on the bends.

"They'd go out on his boat sometimes too. He said that Lawrence was nice enough but quiet." Ray's dad, who died in 1981, was quiet too. "This was before I was born – I'm 68 – and I would have liked to have asked Dad more but he wasn't a talker."

A person who enjoyed a bike ride with Lawrence was a city MP he befriended – Nancy Astor. "A fine woman," was Lawrence's verdict.

"Shaw knew some very influential people: Lady Astor – she would ride pillion on his motorbike – and the Earl of St Germans," says George.

"He would cruise up the river and they'd have lunch at Port Eliot with Lord Eliot. He would go up the Tamar and have dinner with Earl Mount Edgcumbe at the family's

How do those connections square with Lawrence trying to avoid his past and keep a low profile?

"He was sometimes a bit naughty," says George. "He would be A/C Shaw when it suited him and friends with the aristocracy when he wanted to get on.

"He was friends with Hugh Trenchard, the Chief of the Air Staff, the 'father of the RAF'."

He was also close friends with Wing Commander Sydney Smith, RAF Mount Batten's CO – they knew each other from Egypt – and his wife Clare.

Lawrence clearly enjoyed his leisure time. He wrote about "that quaint district, that Barbican, it is full of old streets". He liked to stroll through the waterside district with EM Forster when the author of A Passage To India came to the city to visit an aunt.

On the water he would race a boat in Wembury Regatta.

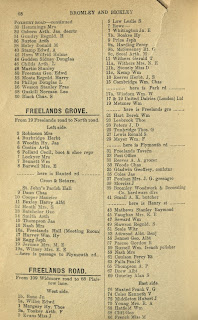

He lived on the base for most of his time at RAF Mount Batten although later had an address in Plymstock.

There are many stories about Lawrence's time off, but he was also a skilled and valued air force

He helped develop the fast launches essential to the emergency service

Lawrence had a fondness for Plymouth. He described his time in the RAF as his "golden years" and Mount Batten was his longest single posting.

Rory thinks that Lawrence's affection for Plymouth might even have pre-dated his RAF service. "I think he knew the city well and had lived here before," says Rory, a former military man himself who lived in South Africa and served until recently in the National Defence Force there.

Perhaps Lawrence had at least been through Plymouth before: he claimed that in about 1905 when in his mid-teens he ran away from home in Oxford and served briefly as a boy soldier with the Royal Garrison Artillery at St Mawes in Cornwall, from which he was bought out. But there is no evidence of that his Army records.

Clare Smith took Lawrence's quote and tweaked it for the title of the memoirs of her friendship with him: Golden Reign.

She doted over him and Lady Astor was similarly close. He kept some personal effects at her home, Elliot Terrace, on the Hoe.

Was there a sexual relationship with either woman? Not if most historians are correct and he was gay – Lawrence himself wrote admiringly about intimate relationships between men in the desert.

Rory, though, believes that Lawrence's reputation was deliberately damaged – homosexuality was unacceptable in those days. He blames elements within the UK Government, a hangover of Lawrence's attempts to give the Arab tribes a homeland, which did not fit with British policy after World War I.

He goes further, subscribing to the theory that Lawrence's death in 1935 was not an accident, but murder.

The facts are that Lawrence, who had left the military a few months previously, suffered fatal injuries on a roadside near Wareham in Dorset, close to where he was then living.

The official accident report said that Lawrence, on a beloved Brough bike, came over the brow over a hill and found two cyclists in his path. He liked to travel fast – he'd once boasted he could get 94mph out of his bike going between Plymouth and London – and had to swerve to avoid them. He hit a tree and died from severe head injuries.

One eye witness said a black vehicle was the cause of the accident. That vehicle was never traced. The witness later committed suicide, ironically while serving where Lawrence had made his name: in the Middle East.

Lawrence expert George Williams says: "Who can say what happened? But Lawrence knew some very famous people and he had contacts at the very highest level.

"King George V sent his personal surgeon to try to help

George has a memento of that day: a copy of Lawrence's last words, sent in a telegram to Devon to Henry Williamson a few minutes before the crash, inviting the Tarka The Otter author to stay.

That is among a large collection based on Lawrence, including more than 100 books.

George, 80, a retired manager in the gas industry

George is saddened that a plaque on a house near the former base at Mount Batten and a bollard on the Hoe are the only reminders of Lawrence's Plymouth connections.

"I'd like to see something on the Barbican where people look out towards Mount Batten to tell them about Shaw and Lawrence of Arabia," he says. "It's a fascinating story."

His own fascination began in 1962 when he saw the film, Lawrence of Arabia. The epic, which won seven Oscars, was largely historically accurate. But there were touches of romanticism and the portrayal of Lawrence was criticised by biographers.

George concedes that it is difficult to separate the man from the myth, whichever name you choose.

How Lawrence settled on Shaw for himself illustrates that point.

"He said he ran his finger through the phone book and happened to stop at Shaw," says George.

"But the author George Bernard Shaw was a great friend – he gave him his first Brough motorbike. Choosing Shaw as a name couldn't have been a coincidence."

"So what do you believe?"

Read more at http://www.plymouthherald.co.uk/Lawrence-Arabia-Plymouth-years/story-19796759-detail/story.html#siTarS7tDd2BTiCk.99

Comments

Post a Comment